Lithuanian Folk Art

“Folklore and folk art keep a nation alive. They alone are the essence of a nation, they alone help prevent annihilation, they alone differentiate one nation from another.”

“Folklore and folk art keep a nation alive. They alone are the essence of a nation, they alone help prevent annihilation, they alone differentiate one nation from another.”

Lithuanian folk art is one of the oldest expressions of Lithuanian culture, as is proved by a variety of archeological artifacts. Over the course of time, the tree of Lithuanian culture branched out in three main directions: language, folklore and song, as well as folk art. The latter was influenced by the environment, the climate, various locations and resources, and also customs, which determined the purpose of the object, its form, its unique coloration and variation of pattern.

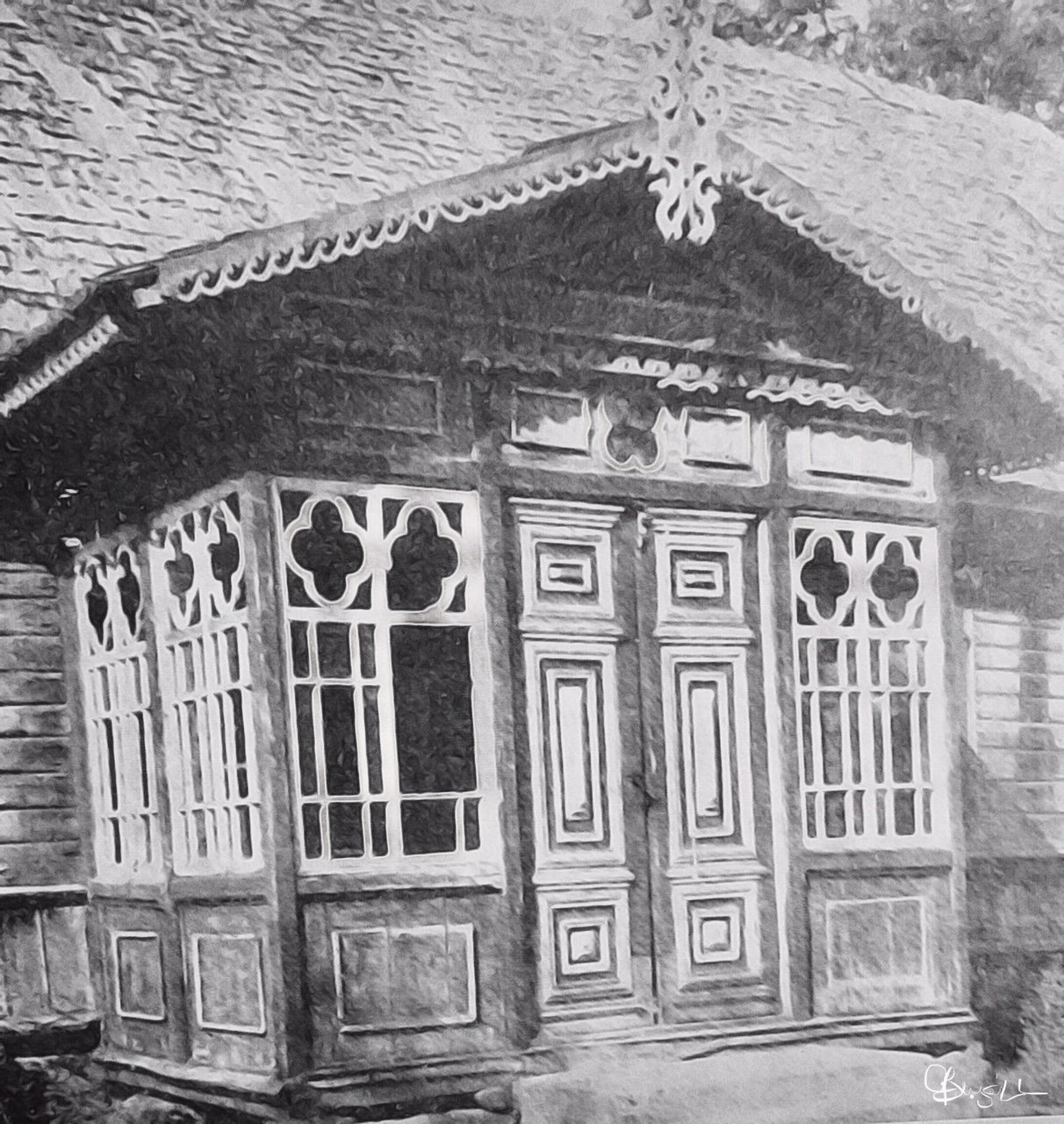

Traditional Lithuanian folk art was essentially developed for the bare necessities of life, when people built their own homes, farmed land, wove all material for clothing, and created works of art to celebrate the seasons. Until the beginning of the 19th century, Lithuania was mostly agricultural – 85% of the population lived on homesteads (farms) or small towns. The peasants followed the traditions of their forefathers and fashioned their daily tools, items and customs for daily life.

In his introduction to the book Lietuvių tautodailės institutas išeivijoje (The Lithuanian Folk Art Institute in the Diaspora, published in Lithuanian), Antanas Tamošaitis also speaks of buildings and tools that the Lithuanians fashioned by hand in distinctive styles. Chapels (in cemeteries and larger homesteads), wooden wayside crosses, farmhouses, furniture, spinning wheels, distaffs, towel racks, shelving units, spoons and other wooden cups and utensils as well as pottery. Other Lithuanian crafts are coloured Easter eggs, straw decorations (šiaudinukai), papercut art, wickerwork, and metalwork ornamentation, crosses and church spires. “Vilniaus verbos” are a unique ornate decoration made of dried flowers and grasses tied and woven together in patterns around a central stalk.

Every household had a hand-loom made by local carpenters, on which the females of the family were expected to weave all the necessary linens and clothing for their family, including their own wedding attire and distinctive sashes.

Folk art was the expression of the homesteader’s soul and his most precious treasure, wrote Tamošaitis. He was very proud of the artistic level of our folk art, and his goal in life, as well as the mission of the Lithuanian Folk Art Institute, was and is to collect, study and preserve ancient folk art as well as to create and foster new folk art.

Lithuanian folk art is traditionally classified in the following categories, although not all of them are practiced in the diaspora.

The art of ceramics is another ancient Lithuanian custom. Village potters had small workshops and provided the peasants with the necessary jugs, pots, plates, candleholders, vases, and figurines. Pottery was glazed and painted with figures of flowers, plants, and birds. Large elegant pitchers were often used to serve mead and beer.

Each potter developed his own characteristic style and made their own glazes. Ceramics were produced in two ways: 1) the pattern was applied to the greenware upon removal from the wheel, or 2) after firing, the pattern was painted on the pottery and then re-fired.

A style of ceramics which is gaining in popularity is the art of black ceramics. Made since ancient times, this is a unique technique using a furnace and smoke from pine logs thrown in the furnace which gives a piece it’s special colouration..

The national costumes were known for the beauty of their colours, variety of patterns, and distinctive style. Until the twentieth century, a Lithuanian girl would weave her own wedding dress and costumes for festive occasions, as well as work clothes. The weaving technique, patterns, colours, and cut of national costumes are categorized according to seven regions of Lithuania: Aukštaitija, the Vilnius region, Dzūkija, Zanavykija, Mažoji Lietuva (Lithuania Minor), and Žemaitija (Samogitia).

Lithuania is known as the Land of Crosses, and is famous for the Hill of Crosses near Šiauliai. The countryside is dotted with many ornamental wooden crosses and miniature chapel-posts or shrines erected at crossroads, in front of homesteads, and in cemeteries. They vary widely in style and ornamentation, and are an art form in themselves. There is a specific word for the folk artist who makes crosses: “kryždirbys”. The carving of crosses (cross-crafting) was recognized as a UNESCO Immaterial World Heritage art as of 2001.

The famous Hill of Crosses, a pilgrimage site for several hundred years, is a testament to Lithuanian faith and perseverance. During Soviet rule, the crosses were destroyed with bulldozers more than once, and locals would rebuild them almost overnight. There are over 200,000 crosses on the Hill.

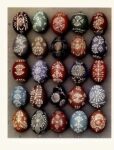

The colouring of Easter eggs with natural dyes was a very popular tradition among the peasants. Either a pattern was applied to the egg with wax before dyeing, or else the whole egg was dyed first and patterns were made by scratching away the dye in certain areas with pointed tool. The ornamented eggs were used as decorations for the festive Easter table and as gifts. The patterns used for eggs decorated with wax are distinct from the motifs and composition used for the scratch technique.

Gintaras, or Amber, has been important to Lithuanians and Baltic people for millennia. Important in terms of culture, art and symbolism. Amber is a natural organic mineral that has it’s origin in ancient resin from coniferous trees and is essentially fossilized tree resin. Amber has specific properties that differentiate it from other materials and can include include air bubbles, or bits of plant, insect or animal material.

Baltic tribes used amber as early as 2000-1800 BC to craft jewellery and weaving tools, treat diseases and protect people against evil spirits. It was also used in ancient trade within Europe. Beautiful jewellery such as necklaces, brooches, earrings and rings have been made and handed down within families. This continues with fabulous modern interpretations of amber jewellery and art.

Other Lithuanian folk art includes work in wrought iron. Iron crosses and church spires are often used to decorate cemeteries, monuments and memorials. Many of their motifs hark back to pagan times and represent the signs of celestial bodies, the sun, and the crescent moon. They adorn many churches and are found abundantly in church cemeteries in Lithuania.

Blacksmiths also forged tools and other farm and household items.

In Lithuania, paper cutting has been practiced as an art since the 16th century (some sources say – the 14th) and was especially popular for decorations at weddings and other special events. By the end of the 19th century, it was widely used as decoration for the home – to cover a window, trim a shelf, a lamp or a mirror frame.

The art form can vary from simple designs that a young child would make to very complex works of art that resemble lace.

Lithuanian Christmas tree ornaments have been made from natural wheat or rye straw for centuries. During months when there were no fresh flowers to decorate their homes, Lithuanians created their own decorations from straw, plentiful on every farm. At Christmas, evergreen branches, garlands and evergreen trees decked with smaller straw ornaments were the holiday decorations of choice for the home.

Larger composite mobiles (or chandeliers) made of many straw ornament shapes were known as a sodas (or garden) and were made for various special occasions such as weddings, birthdays as well as Easter and Christmas.

Until the 20th century there were no textile mills in Lithuania. Peasants would spin linen and wool, and weave all their own cloth to make their garments, bedspreads, bed sheets, towels, and tablecloths. Sashes were woven not only for use as belts, but also as gifts and special mementos. Each family had its own loom. The custom was that a bride would take to her new home at least two dowry chests of woven cloth for the future needs of her family. These were her riches, and a matter of great pride. Lacework, knitting and crochet are still very popular, and the traditional patterns often echo the motifs used in weaving.

Simply but profusely carved towel racks, distaffs, spoon holders, and spoons, along with the spinning wheel, loom, and decoratively painted dowry chests, contributed to the cozy home atmosphere.

Today statues carved out of large tree trunks in the form of folktale characters and pagan gods and goddesses can be found in parks and walking trails around the country. A popular example is The Hill of Witches (Raganų kalnas) on the Baltic Sea Coast.

In Lithuania, knitting was traditionally not considered a very important craft. Every woman knew how to knit, …but spinning and weaving – especially of linen — were the skills that gave a women prestige in the community. Much more weaving that knitting needed to be done, because knitting was used only to make small accessories that would warm hands and feet: socks, mittens, gloves and wrist warmers. …they knitted for special occasions, including holidays and weddings, making small accessories that displayed elaborate patterning and meticulous workmanship.

An artisan specializing in knitting. She taught a knitting workshop at the LTFAI AGM several years ago and fell in love with the organization. Not only is she a prolific author of knitting books, with “The Art of Lithuanian Knitting” under her belt, but she’s also the creative genius behind our social media presence.

An artisan specializing in knitting. She taught a knitting workshop at the LTFAI AGM several years ago and fell in love with the organization. Not only is she a prolific author of knitting books, with “The Art of Lithuanian Knitting” under her belt, but she’s also the creative genius behind our social media presence.

Donna weaves her magic into our online world, managing the LTFAI Facebook page with finesse. Donna has also enlightened us with her workshops and riveting LTFAI Talks.

Traditional Crosses in Lithuania:

Traditional Crosses in Lithuania:

Lithuania is sometimes called the land of crosses. Crosses and unique pillar shrines with various sculptures have been an integral part of the Lithuanian landscape for several hundred years. They represent not only religious symbolism but national identity especially in times of repression. We will look at and discuss the amazing wooden carving and iron work of this important folk art and touch on the well known Kryziu Kalnas (Hill of Crosses) site in Lithuania.

Wool (Vilna):

Wool Crafts in Lithuania: Although linen features prominently in Lithuanian folktales and folk songs, we rarely hear about wool. However in the cold climate working with wool was an integral part of daily life forrural villagers in Lithuania. Small farms were self-sufficient; little or no money was needed to supplement the household’s home production. All the women and girls in a family spun, wove, knitted, and felted wool to create all of the households woolens.

Easter Palms (Verbos)

Easter Palms (Verbos)

History and Significance of Verbos in Lithuanian Life: Palm Sunday is an important part of the Easter tradition. Learn about the history of decorated palms and get to know the customs and decorative techniques specific to Lithuania. (Please note, this is not a hands-on workshop.)

Black Ceramics (Juoda Keramica)

Black Ceramics (Juoda Keramica)

History and use of black ceramics in Lithuania: The tradition of black ceramics has been documented in Lithuania for centuries. Although eventually falling out of favour due to other pottery techniques, Lithuania is one of the few places that still make this beautiful pottery. Learn about the history, techniques and artistry of black ceramics.

Amber (Gintaras)

Gintaras – Our Golden Heritage: Gintaras, or Amber, has been important to Lithuanians and Baltic people for millennia. Important in terms of culture, art and symbolism. Learn about various aspects of Amber to bring you to a new and better understanding and appreciation of this beautiful “golden stone”.

Easter Eggs (Marguciai)

Easter Eggs (Marguciai)

History and Significance of Easter Eggs in Lithuanian Life: The egg has long been seen as a symbol of fertility and life. Learn about the role of decorated eggs in ancient and modern times. Get to know the customs and decorative techniques specific to Lithuania.

We are excited to launch our online LTFAI Talks. We hope to have a series of talks on topics that are relevant to Lithuanian folk art. These are lectures, not workshops, that will provide interesting information for anyone interested in folk art.

We are excited to launch our online LTFAI Talks. We hope to have a series of talks on topics that are relevant to Lithuanian folk art. These are lectures, not workshops, that will provide interesting information for anyone interested in folk art.

They will be from a half hour to a full hour in length with time for discussion at the end.

Each LTFAI Talk is free but you have to register to get an invitation to the session.

Raised in the Lithuanian community in Hamilton, Ontario. He moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, to attend university and was a long-time board member of the Lithuanian Canadian Community there and now serves as the resource person for inquiries about the Lithuanians in Manitoba. Giles has over 30 years of experience in municipal heritage conservation planning and public outreach, having retired as the City of Winnipeg’s Senior Planner for Heritage. He is also a current member of the LTFAI Board.

Raised in the Lithuanian community in Hamilton, Ontario. He moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, to attend university and was a long-time board member of the Lithuanian Canadian Community there and now serves as the resource person for inquiries about the Lithuanians in Manitoba. Giles has over 30 years of experience in municipal heritage conservation planning and public outreach, having retired as the City of Winnipeg’s Senior Planner for Heritage. He is also a current member of the LTFAI Board.

Ramune is a translator and editor, who worked with the Canadian Lithuanian Weekly Tėviškės žiburiai as managing editor for over 20 years.

Ramune is a translator and editor, who worked with the Canadian Lithuanian Weekly Tėviškės žiburiai as managing editor for over 20 years.

She is also an artisan who makes mosaics and jewellery using Lithuanian motifs and amber. She is a long time member of LTFAI and has recently served on our board. She learned tapestry-weaving from Aldona Vaitonienė, a master weaver in Toronto, Canada.

Testimonials: My first ever tapestry. I am an artist so I did a little extra with the beads and wire cord to hang. It reminds me of a dress so I had fun with that thought. 😉

I think you did an excellent job with the workshop, especially for those of us with no experience weaving. I have already ordered yarn. The colors in this piece was whatever my friend gave me as I was not able to go out shopping.

Newsletters will include events, online events, crafting classes, and talks about Lithuanian heritage topics.

To take full advantage of our events, become a member for only $20.00 (USD) / $15.00 (CAD) a year.

Emails are sent monthly.